Esquire

The Russo Brothers Have Post-Avengers Grand Plans

To hear Joe and Anthony Russo tell it, they’re just two hardworking brothers from Cleveland who directed four of the biggest Marvel spectaculars, including the imminent Avengers: Endgame. Now they are taking on an even greater challenge: building a new studio from scratch. (See what can happen when you grow up movie-mad?)

By Rich Cohen | April 22, 2019

If this were a movie instead of a magazine piece about the directors Anthony and Joe Russo—who, in the course of a twenty-year career, have helped fashion two network-TV cult hits (Arrested Development and Community), three feature-film comedies (including Welcome to Collinwood and You, Me and Dupree), three Marvel blockbusters (Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, and Avengers: Infinity War), and another sure-to-be Marvel blockbuster (Avengers: Endgame)—it might begin like this: The stakes are nothing less than the universe itself. And not just any universe, but a particular universe, Hollywood, where the midsize movie seeks to survive the change from pre- to post-Anthropocene, a time of dying, after which the cinematic landscape is seemingly fit for nothing but Marvel stompers and their superhero competitors at DC.

In Infinity War, which grossed more than $2 billion worldwide—the first superhero movie to do so—the protagonists are a group of disparate artists (the Avengers are artists!) who, though squabbling, come together to protect an endangered world. In Russo World, it’s friends and brothers (also artists!) who have come together to form AGBO, an independent film studio now under construction in downtown Los Angeles. The complex will fill three buildings, sprawling across an entire city block. It will house writers, directors, producers, and editors—plus stages, screening rooms, postproduction facilities, and a catering kitchen—in an attempt to replicate the all-inclusive movie factories of yore, those chimeras of an ancient Hollywood dream, lost when the talent agents (see: Lew Wasserman) broke the old star system. In short, the Russos aim to turn directorial success into power, to become moguls of the artistic variety, backed by a $250 million investment from China. “We’re taking everything that we’ve learned from all our time in the business—as independent filmmakers and television directors, as big commercial filmmakers, doing drama, doing comedy, shooting on shoestring budgets, shooting on the biggest budgets of all time—and trying to apply that to the business so we can curate really thoughtful stories,” Joe told me. In this way, the Russo brothers will return to their roots, the midsize moviemaking they forsook to ride the Marvel train.

Like any such story, it’s about redemption.

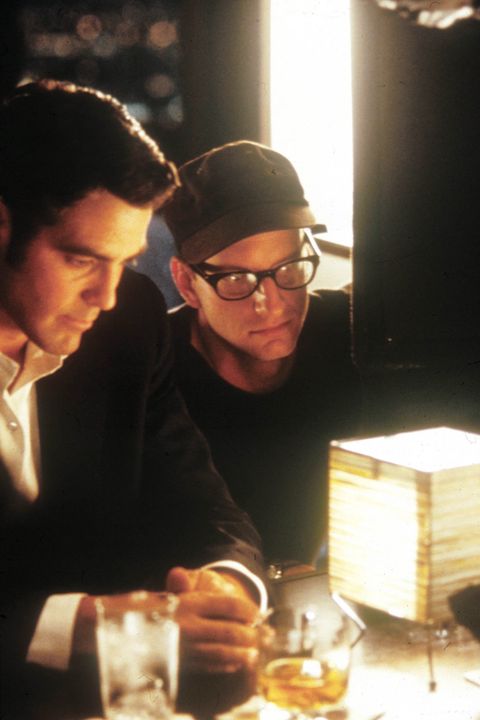

This setup would be followed by a few quick establishing shots of the Russos going about their everyday business. One is tall and thin, with dark, wavy hair; thick glasses; and a conspiratorial grin. Anthony.

The other is shorter and thicker, sincere and intense, but aware of the comedy behind this intensity—Marlon Brando as played by John Belushi. Joe.

We’d see Anthony, forty-nine, a husband and father (Joe calls his big brother “Anth”), tooling around in his surprisingly humble Volkswagen, vanishing into his city as all superheroes must when they assume their secret identities. Then we’d see Joe, forty-seven, also a husband and father, wandering the kitchen of the restaurant he owns on South Hewitt Street (a mile from AGBO) and checking out each dish. In an ideal world, the meal would be arranged in the way of a movie: setup (appetizer), climax (entrée), aftermath (dessert).

Once the characters had been established, the movie would go straight into the backstories—I know I’ve carried this conceit a little far, but it’s fun for me—what, in the superhero biz, they call the creation myths. In this case, because it’s a two-hander, the stories would intertwine like the double helix of their already-intertwined DNA.

Like all legends, it starts not with a person but with a place and a time. Cleveland, the late seventies. The city is falling apart. It’s a hymn of industrial rot and ruin, the glowering sky hanging above the polluted waters of Lake Erie. If that mood, rust and apocalypse, gets into your psyche when you are eight or ten years old, as Joe and Anthony were back then, it’ll stay there forever.

Ask the brothers themselves to account for their taste and they invariably come back with the same answer: “Cleveland.”

“Cleveland went bankrupt in the seventies,” Joe told me. “So our memories are vivid with urban decay, people out of work.” The resulting sensibility turns up in every one of their movies. The Avengers takes place in a world quite unlike the industrial Midwest, but it’s there even so, in the predicament of a threatened society protected by a handful of flawed, possibly overmatched heroes. In other words, Iron Man is not all that different from Basil Russo, Joe and Anthony’s father, a renowned politician in Cleveland—the majority leader of the city council and a Democratic candidate for mayor in 1979, running in a time of strife and insolvency. Cleveland, which had gone into default on December 15, 1978, was the first major American city to skip out on its debts since the Great Depression. Basil was defeated in the primary by incumbent Dennis Kucinich and by the eventual winner, Lieutenant Governor George Voinovich. That was childhood for the Russos: grit, churn, stump, and steel.

“The Ohio factor is critical,” said Robert Downey Jr. (Iron Man) when asked to analyze the brothers. “And, by the way, they don’t come from some salt-free bloodline either. There’s a larceny and some oddball stuff going on back there in the Russo clan.”

Which made it strange to see the brothers here, in downtown L. A., in this fantasy world, as far as you can get from the Cleveland of 1979. We were in a conference room at AGBO. (They plucked the name of their company at random from an Ohio phone book—as in, close your eyes and point.) There was an Avengers pinball machine in the next room; offices down the hall; a snack closet filled with chocolate, granola, and Lucky Charms; and a pool table that no one seemed to notice. (Having it is cool; having it and not playing it is even cooler.) The table between us was covered with the sorts of books that might come in handy to a writer researching for a Marvel screenplay: 100 Deadly Skills: The SEAL Operative’s Guide to Eluding Pursuers, Evading Capture, and Surviving Any Dangerous Situation; 100 Deadly Skills, Survival Edition: The SEAL Operative’s Guide to Surviving in the Wild and Being Prepared for Any Disaster. Now and then, the brothers looked over my shoulder and out the window. Here’s the view: trees, low-slung blocks, warehouses, office towers, and then, far away, snow-covered mountains that form a hard line between the present and the past, the East and the West.

I was later taken on a tour of the new sections of AGBO, what’s being built across the alley. There will be offices with more nice views; public spaces; a screening room; and a big, lasso-shaped bar, like something from a western. The Russos are building AGBO as a kind of rec room where anyone with a good idea will be welcome. It’s the Ohio family thing taken pro. It’s dream Cleveland, everyone together, spitballing their way toward perfection. It’s Hollywood as the Russos imagined it when they were eight and ten years old. Only that Hollywood did not exist, so they’re building it.

Anthony and Joe were surrounded by family in Cleveland: two sisters; innumerable aunts, uncles, and cousins; and still more distant relatives, who, now and then, in the way of unexplained illnesses, turned up, the result being the jagged oddball energy evident in their best work. (See: the tenth episode of the first season of Arrested Development, in which Buster sends George-Michael to score dope to treat Lucille Two’s vertigo; or the eighth episode of the second season of Community, in which members of the study group search for a pen thief—one of their own!)

Patricia Russo, Anthony and Joe’s mother, gave the boys their tremendous confidence and sense of ease in the world. Basil, the politician father, prodded them toward angst. He loved his children to distraction and, because of that love, feared for them, too. His grandparents had been immigrants, which made Basil suspicious of any career that could not be easily defined. Why produce something that no one needs? Moviemaking fell squarely into this category, as did storytelling in general. Good for the family, not so good for the street. A man needs a profession.

Fortunately for Captain America, the Russos had another influence: the local movie theater, the Cinematheque, the sort of art house where nearly everything is in French or Italian. The boys spent their high school years watching Fellini, Truffaut, Godard.

“Our diet was foreign film,” Joe told me. “We loved French new wave, the Italian neorealists.”

“We liked big commercial movies as well,” Anthony said. “We were Star Wars fanatics like everybody else.”

“The Godfather,” Joe added.

The Russos don’t finish each other’s sentences so much as they pick up and amplify. “My favorite thing is watching them bicker,” Downey told me. “They go right back to being eleven years old.” To my mind, interviewing the brothers is like listening to two guitars: lead (Joe) and rhythm (Anthony).

“We watched The Godfather on Christmas,” Joe said.

“Our dad loved movies, so we had a tradition of staying up to watch the late show,” Anthony said. “Old comedies, The Maltese Falcon, the Bowery Boys.”

The Russos came to hold one value above all others: Don’t be boring! You might be spreading a message of world peace, but if you lose your audience in the process, no one’s going to hear it. You see this all over their work—they aim to subvert, surprise, and otherwise fuck with their audience. “We weren’t Steven Spielberg making accomplished films at age twelve,” Joe said. “We were just two guys who loved movies.”

Even if they had wanted to make a film, no one could tell them how, so they went to college instead—Anthony to the University of Pennsylvania, where he started in business (because money) and then switched to English (because fuck money), and Joe to the University of Iowa, where he studied English. They continued on to graduate school at Case Western. Anthony was studying law, with plans to follow his father into politics. Joe took up acting, because the younger brother gets to ride the windbreak created by the older brother and thus do what he wants as opposed to what is wanted of him. And there, in Ohio in the early nineties, it happened.

“Anthony realized he hated law school, and I realized I didn’t wanna be an actor,” Joe said. “Robert Rodriguez had made El Mariachi for $7,000. That inspired a wave of young filmmakers to max out their credit cards and try to grab a lottery ticket.” Anthony told his father he was dropping out of law school. Basil was so angry that he did not say anything at all. The silent treatment. “He eventually, maybe six months later, flipped and was all right,” Anthony told me. “He could tell how dedicated we were.”

“ ‘If you’re gonna do it, do it the best you can,’ ” Joe remembered his father saying.

Their first screenplay came out of their own experience. “Our uncle had this hair salon that we kind of grew up in,” Anthony said. “We came up with this idea of three brothers who worked there but were thieves on the side. It was completely absurdist, very aware of itself as a movie.”

“We cut to the script in the middle of the film,” Joe said.

“It was us trying to say, ‘Here’s everything we love and hate about movies,’ ” Anthony said.

“There’s a riotous spirit in it that’s full Cleveland,” Joe said. “It’s sorta like, ‘We don’t care—what do we have to lose?’ ”

They started with a basic misapprehension: that making a movie would be cheap, easy. They bought a camera and other sundries on credit, a debt they would not repay for years. Family and friends did much of the acting. But Robert Rodriguez must have left out something important, because, though they scrimped, they quickly ran out of money. “We couldn’t afford to develop the film for six months,” Joe said. “It sat in a refrigerator in our garage. Had there been a blackout, we would’ve lost the entire movie.”

“That was around the time when things were starting to convert from flatbed film editing to digital,” Anthony said. “We borrowed our cousin’s van and drove to New York and picked up a Steenbeck”—an old-style film-editing rig—“for a couple hundred dollars.”

“Which weighs hundreds of pounds, a giant old machine,” Joe said. “We carried it up three flights into my apartment. Had it in the room, so my poor wife”—Joe married young—“had to live with me for two years in this apartment in Cleveland where we had film hanging everywhere, and film has a very distinctive smell. You could smell it at night when you were going to sleep.”

Out of cash and credit, they decided to apply to film school, because film school meant access to student loans. Plus equipment, which they could use to finish their movie. That was their only focus in ’93, ’94: Finish the fucking thing. Anthony, the Ivy Leaguer, went to Columbia. Joe, the Big Tenner, went to UCLA. Working in tandem, long- distance, they finished their first movie, Pieces, in 1996. They describe it as a rip-roaring hometown caper. It was never released.

But Pieces did get into Slamdance in 1997. The theater was full at first, but when the lights came up at the end, there were only two or three people left. One of them happened to be Steven Soderbergh. “We didn’t even know he was there,” Anthony said. “He snuck in and snuck out and called later.”

“When I saw that film, I recognized an incredible amount of energy, imagination, and confidence and at first just wanted to know more about them—who they were, where they came from,” Soderbergh told me. “So I started as a fan.”

“We had lunch at a Cuban restaurant called Versailles” in Los Angeles, Anthony recalled. Soderbergh said he loved their film and wanted to help them make another.

“I quickly realized we were kindred,” Soderbergh said, “and so the question was natural: ‘What do you want to do next?’ ”

“It was interesting,” Anthony said. “We had spent time in school and had grown up at the Cinematheque, so we were entrenched in the art-house point of view—that thematics were more important than narrative, that riotous techniques were more interesting than traditional techniques. Soderbergh was a god in that regard. He’d made Sex, Lies, and Videotape and Kafka and King of the Hill and basically pointed a middle finger at the business. He’d gone on this interesting journey, and we were sitting with him at lunch just asking about his career and how it was going and he said, ‘Not well, because Kafka and King of the Hill and all these movies I’ve done since Sex, Lies, and Videotape have not made money.’ He said, ‘Guys, it’s called show business,’ and told us, very honestly, if you don’t know how to make people money, you won’t work very long in film.”

Soderbergh was probably talking to himself as much as to the Russos, because he then said, “I’m gonna make a genre movie with George Clooney.”

“Anth and I were like, ‘Why?’ That’s when he gave us the speech about it being called show business,” Joe said. “We went and saw that movie when it came out a year and a half later,” Joe added, referring to 1998’s Out of Sight. “We thought it was his best, and thought, Wow, maybe we’ve got to reject these pretentious notions of what storytelling needs to be and start figuring out how to tell more popular stories.”

Soderbegh became a mentor and a model for the brothers, who left school and resettled, for a time, on the director’s couch. They began working on Welcome to Collinwood, which starred top-drawer actors: George Clooney, William H. Macy, Sam Rockwell. It was the first of two released features the brothers made before heading to Marvel. Their 2006 comedy, You, Me and Dupree, with Owen Wilson, Kate Hudson, and Matt Dillon, was more successful, but neither movie did gangbusters. It was in another medium that they’d find their voice. The Russos may in fact be the most successful example of a new breed of filmmaker, whose eye comes from cinema but whose sensibility comes from television. Seated before the idiot box at eight, ten, eleven years old, they had soaked up the tropes of the old sitcoms they loved: Gilligan’s Island, My Three Sons.

That would stand them in good stead in 2002, after Welcome to Collinwood bombed and, for a moment, it seemed they were washed up right from the start. This was when The Sopranos was ascendant. Wake of 9/11. Everything broken. Every broken thing being formed into new patterns. The Sopranos played less like a show than like a movie. Not just the subject matter but the texture. The TV networks, needing to stay in the game, began to look to the feature world for help. Not wanting to pay for Scorsese-caliber directors—that time would come—they turned to the booming world of indies. Same aesthetic, half the price. And so the Russos, then with only a flop and an unreleased film to their credit, found themselves in demand. “We got a show on FX called Lucky and shot it single-camera, handheld,” Joe said. “We made it super edgy. At the end of the pilot, we’ve got John Corbett crying to his ex-in-laws as he hands them money for his wife, who died of a drug addiction that he didn’t stop. There wasn’t a lot of stuff like it on television. It got the attention of Ron Howard, who was developing Arrested Development. I think he knew he needed young, aggressive indie filmmakers who could execute this crazy show.”

Arrested Development, about a spectacularly dysfunctional family, was created by Mitchell Hurwitz, a veteran of the sitcom wars who had worked on The Golden Girls. “I had the pilot outline and I’d given it to fairly prominent TV directors, and none could make heads or tails of it,” Hurwitz told me. “The Russos got it right away. The pilot looked, to most people, too big, too wild and expensive. But the Russos did not want to scale it back. They wanted to go the other way—make it bigger. They kept saying, ‘Don’t let the network people intimidate you. We can do this.’ ”

Howard, the show’s executive producer, saw in the Russos an opportunity to rejuvenate the sitcom.

“He wanted thirty locations in the pilot alone,” Anthony said. “In case you don’t know the business, let me just tell you: That’s insane.” On a typical nineties sitcom—Friends, say, or Seinfeld—five locations per episode was closer to the norm.

“One location change a day is about what a traditional production can handle,” Joe said. “But we didn’t say no. We said, ‘If we can come up with new rules’. . . So we said, ‘Okay, here’s how we’re gonna do it. . . . We’re not gonna shoot on film; film is so expensive. We’re gonna use digital video cameras, the kind they use for news.’ No one had done that before.”

“Fox panicked,” Anthony said. “They said, ‘It’s gonna look like a shitty documentary.’ We said, ‘We want it to look exactly like a shitty documentary.’ ”

The Russo-directed pilot divided the network. The old hands, people with power, hated it. Fast, dirty, anarchic. It did indeed look like a shitty documentary. The younger people loved it and pressed for its release.

In its first incarnation—the show was revived by Netflix in 2013 and again in 2018—Arrested Development aired for just three seasons (2003–06), with the Russos directing multiple episodes. Like many of their early projects, the series was a critical success and a commercial disappointment. But it became a cult hit and won the brothers an Emmy for directing, which would turn out to be a kind of free pass in the coming age of peak TV. What’s more, working on the show was a crash course in the art of television, which is as different from traditional filmmaking as tennis is from tug-o-war. Whereas film, in its classic conception, is all about the auteur controlling every detail, TV is about collaboration, sharing work and credit, fulfilling a group vision—ideal skills for anyone looking to join up with Marvel.

“We could’ve stayed in TV forever,” Anthony said.

“We love TV,” Joe said.

“We were raised on TV,” Anthony continued.

“Dobie Gillis,” Joe said.

Their springboard to Marvel was another series, Community. That show was based on the life experience of its creator, Dan Harmon, who grew up in Wisconsin and went to community college in California. The Russos recognized their sensibility in the material: midwestern stasis, months spent between nowhere and nowhere else. Community debuted in 2009 on NBC and ran for six years; the brothers served as producers during the first three seasons and again directed multiple episodes. It found its footing with a parody episode toward the end of season 1: a school-wide paintball battle filmed as if it were a John Woo action flick. Over time, Community gave itself over to this sort of parody, with episodes playing like hymns to all the classic movie genres: the war movie, the prison movie, the postapocalyptic Mad Max–type movie. If a producer happened to be watching these episodes—he was; his name was Kevin Feige, and he was the president of production at Marvel Studios—he would’ve seen that the Russos had mastered all the mechanics of big-time Hollywood.

“The paintball episode was a spoof of the action movies we grew up on,” Joe told me. “It was wildly successful with the fan base. So at the end of season 2, we did another, based on one of our favorite filmmakers, Sergio Leone. It was called ‘Fistful of Paintballs.’ ” Feige, who is a student of pop culture and was obsessed with Community, watched it and thought, Man, these guys understand comedy; they understand action. They should be working at Marvel.

Back when the Russos were growing up, Marvel appealed to the strangest, geekiest, most subterranean of shy kids—metalheads, outcasts. Superman, owned by DC Comics, was clean, handsome, and well-adjusted. No flies on him, no flaws. The Hulk, a creation of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Marvel, was twisted in comparison, a rage-wrecked scientist. Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four—all kinda weird and flawed. Marvel characters were accordingly left behind in the first flush of superhero movies: 1978’s Superman and its sequels, 1989’s Batman and its progeny. But as American culture came to seem increasingly warped in the twenty- first century, Marvel gained traction. Characters that had seemed fringe became a mirror reflecting some essential truths about a society entering its terminal stage. The universe of those heroes, Marvel’s intellectual property, suddenly gleamed with hidden value. Rather than sell it off piecemeal, Feige, who became president of Marvel Studios in 2007, decided to build an in-house operation, producing a catalog of connected movies.

The first movie of that series—Iron Man (2008), starring Robert Downey Jr.—created the template the others would follow. Downey, as directed by Jon Favreau, minted the original coin, the bedrock currency of the universe. It was action cut with comedy, wiseguy charm. If you removed all the fight scenes, you’d be left with fifteen minutes of exposition; the basic vibe was the Super Bowl if the Super Bowl were funny. The result, all these movies later (twenty-two and counting), is the most valuable property in Hollywood history, rivaled only by George Lucas’s Star Wars. Favreau was followed by other directors: Shane Black (Iron Man 3), Louis Leterrier (The Incredible Hulk), Kenneth Branagh (Thor), Alan Taylor (Thor: The Dark World), Taika Waititi (Thor: Ragnarok), Joss Whedon (The Avengers, Avengers: Age of Ultron), Joe Johnston (Captain America: The First Avenger), and James Gunn (Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 1 and Vol. 2), among others. By the time Feige went looking for someone to direct the second Captain America, he needed a workhorse who could handle green screen, handle comedy, handle stars, and take care of the legacy, carrying it forward while also bringing something new. In other words, he was looking, though he might not have realized it at first, for Joe and Anthony Russo.

“We got a call from our agent one day saying, ‘Marvel’s got a list of ten directors and you guys are on it,’ ” Anthony said.

Here’s what the studio did not know: The Russos had a lifelong Marvel passion.

“We grew up collecting comic books,” Joe said. “I still have my collection. All Marvel.” “Joe was more into comic books,” Anthony said, backing away. “It was his thing. I was more into fantasy.”

“He used to carry Lord of the Rings like it was the Bible,” Joe said.

The Captain America pitch: It was a tough nut to crack. In most cases, you’re trying to sell a new character or scenario, or revive a moribund property. (Think Ryan Coogler and Creed.) The Russos had to sell themselves as shepherds of an already-lucrative franchise. On top of that, Captain America is the straightest character in Marvel. But they declined to play it safe. “We came in and pitched a radical reinvention of that character,” Joe said. “I said, ‘Look, when I was growing up reading Captain America, I found him very boring. He’s two- dimensional—characters who don’t have a personality flaw are difficult. You can tell one story about them, but once you try to tell a second, where you have to have some narrative movement, you run out of gas. So we said, ‘Look, he’s been frozen in ice. He’s gonna wake up in modern times. We feel like we could use that as a reset. We can reset the tone and the character. We can create emotional complexity.’ ”

“How do we subvert him and reinvent him in a way that’s interesting?” Anthony said.

“Captain America is a guy dressed in a flag who refuses to quit,” Joe said. “From a narrative standpoint, that’s easy to understand. What we find interesting is deconstructing that.

“We pitched Captain America meets 3 Days of the Condor,” Joe continued, referring to the 1975 Sydney Pollack movie in which the CIA tries to kill its own agents. What if a man with all the old World War II–era values—honor, honesty, integrity—turned up in contemporary America? The character is still good; the world has gone sour. That’s the movie the Russos wanted to make.

“We called Soderbergh and asked, ‘Will you call Kevin Feige and vouch for us?’ ” Joe said. “Soderbergh said, ‘Why do you want to make a comic-book movie?’ I said, ‘Steven, I still have my collection.’ ”

“I remember it as an email,” Soderbergh said. “I told Joe I wanted to talk to him first. I wanted to find out why they wanted to make a Captain America movie. I wanted to make sure it was because they really wanted to, not because there was someone in their ear. I got Joe on the phone and he started telling me about his comic-book collection, and I was like, ‘Okay, okay, okay,’ and made the call.”

“Stories that had an impact on you as a child have a special place in your heart forever,” Joe told me. “That was true with these stories for us. There’s an essential mythology to them we thought we could infuse with thematics and reach a wide audience. We’d been on this crazy journey as storytellers. . . . We’d done all kinds of weird shit. We’d done Pieces, which was totally nuts. We’d done Welcome to Collinwood, which was a weird comedy. We’d done Development, which was absurdist in nature. We’d done Community, which was absurdist and deconstructionist. Now we wanted to try something populist.”

For most directors, two Marvel movies in a row would be the limit. The work is famously grueling—all those rewrites, all those actors and story lines, sets and locations. Editing one picture can take close to a year. Early this year, the Russos finished their fourth consecutive Marvel film, a Lou Gehrig–like feat. Joe had moved to Atlanta to shoot the last two back-to-back, while Anthony commuted. They saw their kids only during rare off-hours, relieving each other when necessary, at times going insane. And these were not mere Marvel movies—they were Avengers movies, meaning just about every character and backstory in the universe had to be included. That also meant that the brothers had to cope with not just two or three A-list movie-star egos but upwards of two dozen. Moreover, the last two films are capstones on the entire Marvel endeavor.

According to Downey, each Marvel script is identified by a code word—shorthand slang. “You know what it was for Iron Man 2?” he asked, laughing. “ ‘Rasputin’—not the most auspicious name.” Infinity War and Endgame went by “Mary Lou” and “Mary Lou 2” (as in Retton, the gymnast). “With 3 and 4, we had to stick the landing,” Downey explained, “or we were going to destroy the entire universe.” Infinity War ended with the deaths of half the important heroes in the MCU. You can tally it like Capone. Black Panther . . . dead. Spider-Man . . . dead. Doctor Strange, Falcon, Star-Lord . . . dead, dead, dead. And not just any sort of death—they turned to dust, as in the Book of Genesis.

“Mark Ruffalo”—who plays Bruce Banner/Hulk—“was in a theater in New York with his son, who was sixteen, and his friends, and Mark was filming their reaction” to the ending of Infinity War, Joe told me. “Mark was wearing a hat and glasses, hiding. He sent me the video: He is panning around the theater and it’s still half full ten minutes after the movie. People were arguing and there was one guy who’d ripped off his shirt and was wandering the perimeter screaming, ‘Why?’ ”

“You’re dealing with the fate of the world in these movies,” Anthony said. “You’re dealing with heavy issues, but you’re dealing with them in a fantasy realm. You’re dealing with them in a way that’s removed from reality. So I think these movies allow us to access the strongest anxieties and worries and tensions people are feeling but do it in a way that’s one step removed from actual fears and tensions. It’s a safer way to process those emotions.”

“We’re deconstructionists at heart,” Joe said. “We like tearing things down. We came into Marvel at a point where we could be the guys to tear down parts of the story because that’s the natural progression: You build it up to tear it down to build it back up. Winter Soldier tore down the infrastructure. There’s this organization called S.H.I.E.L.D., which had been the good guys. We made them the bad guys. In Captain America: Civil War, we tore apart the Avengers. We took this family unit, tore it apart. In Infinity War, we took half the characters and killed them.”

Think back to their first principle: Don’t be boring!

“You have to surprise people so they have something to talk about,” Joe said. “If they’re not talking about it, it’s not going to be successful.”

The new movie, Avengers: Endgame, should answer the questions left hanging at the end of Infinity War: Can superheroes die? Can a movie studio sacrifice so much wealth for an unexpected kicker or, as on Easter, will they be born again? Secrecy was a premium value on the set. No spoilers. Even the actors were kept in the dark, working on a strictly need-to-know basis. The Russos occasionally operated by disinformation, writing fake scenes and scattering them around. “I would never leave anything in my trailer,” Downey told me. “I would tear up and shred. It’s true that they issued false sides”—i.e., script pages—“and have done counterintelligence work on this stuff.”

Of course, the bigger mystery, the question that really matters, is: How much money will this movie make? If Endgame matches or bests Infinity War’s $2 billion-plus, the directors, though still relatively unknown to the public, will enter the pantheon with George Lucas and James Cameron. But the Russos’ situation is different. Whereas Cameron and Lucas created their own worlds—their own IP—the Russos have merely put their considerable mark on worlds created by others. Arrested Development was created by Mitchell Hurwitz. Community was created by Dan Harmon. The Marvel Universe was created largely by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. At AGBO, the brothers will take on the task of building their own world from the ground up. No one knows if they can pull it off.

If all goes according to plan, AGBO will produce material-driven projects and distribute them in whatever way makes sense—some in theaters, some via streaming services. The Russos will make their own films there while also using the studio to support young writers and directors. One of its first releases, Dhaka, about an Indian criminal kingpin in search of his kidnapped son, is being directed by Sam Hargrave, who was the stunt coordinator on three of the Russos’ Marvel movies.

“Our idea with AGBO is to try to pay back our karma of debt to the universe that we owed Soderbergh for what he did for us,” Joe told me, “and, at the same time, create a space where Anth and I can focus on artist ownership, focus on full creative control over our projects, where we could finance our projects.”

The dream of creating an independent studio, artist-run and free from bean-counter control, is nothing new in Hollywood. “The closest model to what we’re trying to accomplish is United Artists,” Joe said, referring to the studio founded a century ago, not far from AGBO, by D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin. But isn’t that what Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and David Geffen were after at DreamWorks? Or Jerry Weintraub at his failed Weintraub Entertainment? It’s been nearly impossible to achieve—in the past, the established studios were simply too powerful, the challenges of scale and distribution too daunting. Even United Artists, which made films like City Lights, High Noon, Midnight Cowboy, and Rocky, plus most of the James Bond movies, had become a shell of itself by the eighties.

But the Russos believe things have changed. Social media, streaming—all the new technologies have fragmented the monolith. Now, while everyone is reeling, is the time to create a new paradigm.

Still, I asked Joe if he was worried about AGBO, given that the history of independent studios is a history of failure.

He liked their chances, he told me, because their leverage was nearly unprecedented. “We’ve made four Marvel movies in six and a half years and grossed billions of dollars,” he said. “That’s a unique circumstance for filmmakers.”

“And it happened to sync up with a time when the Chinese film industry was looking to move beyond China,” Anthony added. “And our movies are so well-received there, we ended up connecting with the right people—Huayi Brothers, one of China’s biggest filmmaking companies. . . . They wanted to fi